As UX designers, we constantly navigate the fine line between prioritizing the user’s experience and meeting business or legal requirements. It’s a role that demands both creativity and precision, where even small mistakes can have far-reaching consequences.

However, there’s a common pressure to “always be right” or the fear of making mistakes. Depends on the project, we may not always have full context of a project or know all of the stakeholder beforehand. While it’s natural to worry about the ripple effects of our decisions, it’s also important to remember that no design decision is set in stone—and what truly matters is how well our solutions address the problem.

The Importance of Sound Design Decisions

One key lesson I’ve learned over time is that you don’t need to be perfect to contribute valuable insights. What truly matters in product design is that your opinion is well thought-out, based on sound logic and backed by user research, UX principles, and data.

When you contribute to design discussions, it’s essential to have an informed opinion. If you feel unsure, it’s okay to say so, but it’s even better to present a hypothesis that can be tested. The best design decisions solve user problems while aligning with business goals, and are grounded in objective reasoning rather than subjective preferences.

For example, if a design proposal enhances the user experience but doesn’t align with product strategy or is difficult to implement, it may need to be revisited. Great design strikes a balance between user needs, technical feasibility, and business objectives.

Back Your Design with UX Principles

Good design is not about personal preference—it’s about how well it works for the user. Design opinions should always be supported by user research, data, and UX heuristics. Are you making decisions that align with established UX principles like Nielsen’s heuristics or laws of ux? Does the proposed design reflect insights from usability testing or user feedback?

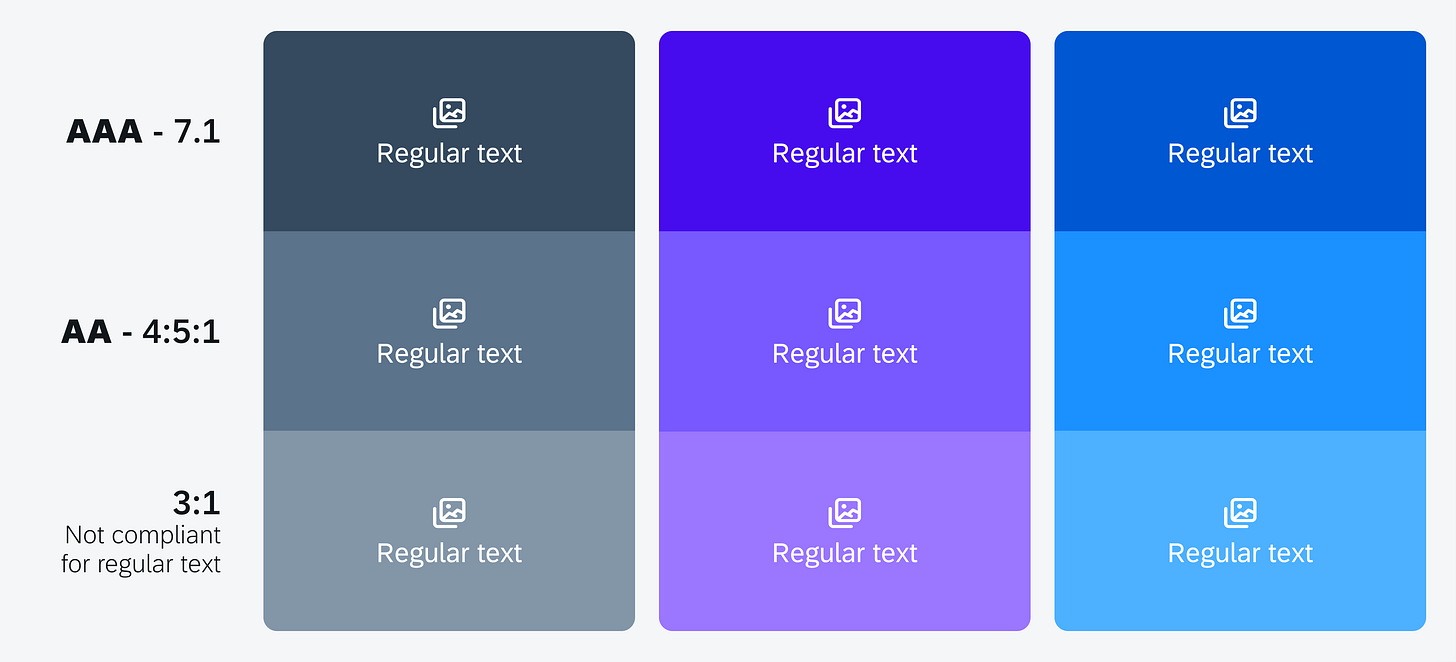

This objective approach ensures that design decisions are rooted in evidence, not just personal taste. Even decisions related to visual design, such as color schemes, typography, or layout, should be justifiable with reasons that align with the overall user experience.

Dealing with Imposter Syndrome

Imposter syndrome is something many designers, even those at senior levels, experience. It’s the feeling that your ideas might not be good enough, or that others are more knowledgeable. But it’s important to recognize that this is often a false narrative. According to a summary in “Imposter Phenomenon” in the collection of National Institute of Health:

“Imposter syndrome (IS) is a behavioral health phenomenon described as self-doubt of intellect, skills, or accomplishments among high-achieving individuals. These individuals cannot internalize their success and subsequently experience pervasive feelings of self-doubt, anxiety, depression, and/or apprehension of being exposed as a fraud in their work, despite verifiable and objective evidence of their successfulness.”

If you’ve studied design, received positive feedback in your career, and delivered successful projects, you’re more capable than you may realize. Design is an iterative process, and being wrong occasionally is part of the journey. What’s more important is that you’re learning and growing with each iteration.

My Experience

When I first started my current job, there was a discussion about improving a component. As a new team member, I jumped in because the existing proposal didn’t fully align with the design goals. My input was well received and ended up being the final solution. It was a good reminder that all opinions are valued despite seniority.

That was also the moment I realized that I didn’t have to be perfectly right. The goal is to propose ideas that make sense and contribute to solving the problem. A well-supported idea, even if it’s imperfect, can still lead to valuable outcomes.

Wrap-Up: Keep Growing as a Designer

As designers, we’re not required to be perfect. What’s important is that we approach every problem with a user-centered mindset, articulate our design rationale clearly, and be open to learning from both successes and mistakes. Design is an ongoing process of learning and iteration.

So, keep thinking about why you design—whether it’s for improving user experience, driving business growth, or both. Continue to learn so you have more knowledge and experience. Continue to practice articulating design decisions.

You don’t have to be right, you just need to be reasonable.